The Story of Civilization

The story of human civilization begins around 10k years ago in the dawn of agricultural societies, in a new relationship between humans and land. Agriculture transformed the nature of land from external environment into direct extension of the human body and society; from something to contend with into something to protect.

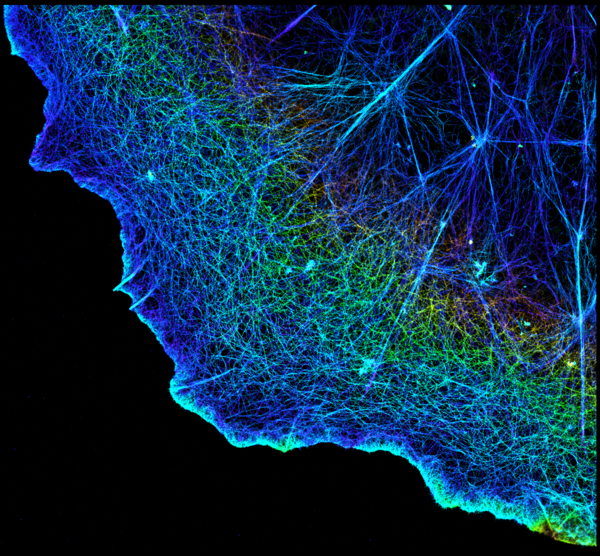

The story is often told, quite wonderfully, in maps; the changing borders of unified claims on land in the form of empires that ebb and flow across the rugged surface of the Earth over the last few thousand years. As an empire evolves physically, driven by mega-political forces of topography, climate, microbes, and technology, it transforms swaths of land from “them” to “us”, and accelerates the flow of information between its internal regions, catalyzing the evolution of culture.

Something notable happens around 2500 years ago: a large number of smaller sovereignties in Europe, Africa, and Asia consolidate into one international entity - the Achaemenid Empire, the first of its kind. Alexander the Great often gets credit for his efforts and successes in uniting the world a few hundred years later, but the Persians had already done most of the work. Alexander was just the Macedonian megalomaniac who showed up and lifted it from them, spreading the Greek revolution in technology and values into the East.

Within a few hundred years of Alexander’s death, the Silk Road would officially open, but the East and West would cease to be united by a common empire for another thousand years. If Alexander brought a few hundred years of early European cultural evolution to the East, it wasn’t until the empire of Genghis Khan, the Modest Mongolian, that a millenium of Chinese cultural evolution was brought back West, effectively ending the Middle Ages and laying the foundation for the Enlightenment in Europe.

Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan often gets a bad rap - a ruthless brute, the archetypal barbarian. But the truth seems to be much more subtle; while he was absolutely lethal in battle, he was far more humane, progressive, and clever than any of his contemporaries. He ran a meritocracy with a strict code of ethics that applied to him as well as it did to anyone else. His power was checked by elections. He preferred to assimilate than to enslave. He distributed wealth fairly. He liberated women. He was driven to upend and flatten the hierarchies of power, of aristocracy and inequality, to promote free trade and freedom of religion, to elevate skill over lineage. But to do so, he would have to become a merciless warrior, leading a merciless warrior nation; to execute swiftly and with lethal effectiveness; to terrify the world.

Genghis Khan, whose actual name is Temüjin, was raised in the school of hard knocks. While Alexander embodied Western privilege as the son of a king and student of Aristotle, Temujin was born in the middle of the 12th century into a society of small, warring, nomadic Mongol tribes; he had to continuously fight for his life.

Temujin’s father kidnapped his mother from another clan. An outsider from the outset, he was born clutching a blood clot, which his mother took to be an immense omen. His father was poisoned to death by the Tatars and his family was abandoned by his father’s tribe. Sibling rivalry would cause him to murder his older half-brother. His young wife was kidnapped and raped. An old friend of his father’s, who served as his own mentor and guardian, tried to have him killed. His best friend, with whom he had sworn a blood oath, became his most bitter enemy.

Cast amidst this rugged upbringing was Temujin’s humble ambition to put an end to the cycles of violence, of attack and counter attack, to unite the warring Mongol tribes. The story of how a nomadic, pre-civilized warrior went on to establish the largest empire in history is an astounding one, told in detail in Jack Weatherford’s Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Much of civilization’s history is interjected with invasions by pre-civilized, nomadic, “barbarian” tribes - the early Hebrews in Israel; the Germanic tribes and the Huns in Rome; the Five Barbarians in China; the Turkish conquests. But the Mongol Invasions and the resulting Mongol Peace were unprecedented in scope.

The Mongolian Nation

Temujin’s rise to power, his weaving of diverse Turco-Mongolic tribes into a unified peoples and ultimately an empire, was marked by his implementation of fundamentally progressive policy changes to reduce internal conflict in the increasingly larger groups he ruled over.

First, as he become khan (chief) of his own minor group, the Mongols, in his late 20s, he elevated loyalty and merit above kinship, appointing important positions based on competency and loyalty, abolishing aristocracy, and enabling anyone to rise through the ranks.

Second, as he expanded his territory to include small neighbouring Turco-Mongolian tribes in his late 30s, he elevated assimilation over slavery or desertion, slaying the aristocracy and marrying the remaining people throughout households in his own clan, even adopting some of them into his own family as siblings to be raised by his mother.

Third, as he worked to assimilate the much larger neighbouring Tatars in his early 40s, he pursued the orderly collection and redistribution of the spoils of war over chaotic and haphazard looting. This allowed for a more complete victory over defeated soldiers before looting began, preventing escape and later counter attacks. It also enabled loot to be distributed meritocratically, including fair allocations for widows and children of killed soldiers.

Fourth, to fully integrate the thousands of Tatars, he radically reorganized the structure of the army and tribe beyond kinship ties by randomly assigning warriors into squads of 10 that were ordered to live and fight as brothers. He organized 10 squads into companies, 10 companies into battalions, and 10 battalions into a tumen, a small army of 10,000, the leader of which he would personally appoint. Thus the modular structure of the army came to transform the nature and life of the tribe by aligning all service and relationships along these lines.

Taken together, these reforms would have the effect of dismantling aristocracy, maintaining loyalty, and improving integration of the different tribes. At this point, Genghis Khan had succeeded in abolishing class distinction - his followers were now one united people: the People of the Felt Walls, in homage to the material that make up their ephemeral nomadic homes.

Nearly 2000 years earlier, Cleisthenes implemented a similar reform in Greece, allocating people into units of 10 to cut through the tribal rivalries of the time and lay the foundation for Athenian citizenship and democracy. While there’s no reason to believe Temujin was directly aware of these efforts, the parallels are striking.

By his mid 40s, after final showdowns with powerful men from his past who ruled the remaining large tribes in the Mongolian plateau, Temujin would be elevated to the status of Great Ruler of the newly formed Great Mongol Nation of over a million people and around 15-20 million animals distributed across the Mongolian steppe. His Mongolian title was Chinggis Khan, Khan of the people of the strong, fearless, wolf. In Persian, it would be Genghis Khan.

To bring further order to his newly formed nation, and to reduce dissent within, Genghis Khan introduced his Great Law. Unlike his contemporaries across Eurasia, who ruled above the law and according to the will of God, the Great Law was a force of meritocracy and applied to rulers, including himself, as well as anyone else. He adopted a writing system, the first among the Mongol people, to help record and administer the law, and established an incredibly efficient public postal service that would come to rank as highly as the military itself.

Via the Great Law, among the Mongol Nation, Genghis Khan banned the kidnapping of women and their sale into marriage; he banned the abduction or enslavement of other Mongols and the stealing of animals; he implemented a lost and found system; he forbade hunting during reproductive seasons; he implemented complete and total religious freedom, and nurtured a diverse mix of shamanist, Christian, Muslim, and Buddhist religions; he exempted religious leaders and other professionals - like doctors, lawyers, teachers, and scholars - from taxes and public service.

All of this was in stark contrast to his supposedly more civilized contemporaries in Europe, Persia, and East Asia, whom he would turn his attention to next.

Mongolian Conquests

The Mongolian army was lethal, and unlike anything the civilized peoples of the world has seen before. It was modelled after the hunt. Unlike the frail peasant armies of cities, the Mongol diet was rich in wholesome protein and fat. They could survive entirely off dried meat and dairy, and hunt for food as necessary, avoiding the need to carry a large food supply chain or to cook meals. They could also more easily fast for a day or two. The recursive structure of their army made them highly fluid - more like a set of concentric circles than a hierarchy of units. They spread out over vast distances, and communicated extremely efficiently, using a mix of silent signals and song.

As a smaller, leaner attack force, the Mongols became masters of psychological warfare, employing trickery, deception, confusion, and propaganda wherever possible to reduce the amount of actual fighting they had to do, and to leverage their enemies against themselves. They would spread rumours to ignite infighting; pretend to retreat and then attack during premature victory celebrations; stampede peasants out of the fields towards the city to jam supply routes. They made extensive use of paper to spread terrifying rumours of how large and ruthless their army was. Their notoriety today is likely much more a result of their own trumped up tales than it is of their actual casualties.

While European aristocrats respected one another and slaughtered commoners, Mongols were more likely to kill the aristocrats. While the Europeans engaged in endless terror campaigns via public torture and mutilation, the Mongols were less about cruelty than about speed and efficiency in military execution, to a degree never before witnessed.

The Mongolian conquests of the world began with the cities of Northern China, who had traditionally dominated over the warring tribes. Cities were offered the opportunity to simply surrender and pay tribute. If they refused, they would quickly lose in war. If they agreed, but then betrayed him, they would be annihilated. It was here the Mongolians perfected the conquering of cities and adopted the Chinese siege technology and gunpowder weapons. Rather than carry such machines along with them, professionals from conquered cities were incorporated across the army into a distributed engineering corps that could assemble the machines as needed from local materials.

Having expanded his empire east to modern-day Beijing, and having secured access to Chinese goods and technology, Genghis Khan sought to engage in peaceful trade with others, especially the Islamic Persian societies to the south west. But when he sent peaceful envoys to the neighbouring Khwarazm Empire to initiate commercial relationships, his envoys were murdered and maimed. Now in his late 50s, Genghis Khan responded with ferocity, annihilating the perpetrators, and incorporating virtually all of Persia into his empire over just a couple years. Though he was always out numbered, even as much as 50 to 1, many cities surrendered or fell within days or weeks. The reported casualties during these conquests are absurdly high, in the tens of millions, though there is little archaeological evidence and they are likely more a result of Mongol propaganda and military effectiveness than real casualties. That said, entire cities were massacred or razed to the ground.

Genghis Khan returned to Mongolia, to wage more war against other Northern Chinese states that had betrayed or wronged him. He would ultimately die there in 1227, in his mid 60s. At this point his empire stretched from North Eastern China all the way across the Eurasian steppe to the Caspian Sea and Persia. It is estimated that his direct descendandts, almost 800 years later, number around 16 million.

Genghis Khan’s heirs, his sons and grandsons, would go on to expand the empire, to cover all of China, southern and western Russia, the Caucasus and eastern Europe, and Mesopotamia. The only thing that seemed capable of stopping the advance of the Mongolian army was heat and humidity, which weakened their bows and caused them and their horses to struggle and fall ill. Hence the topography and climate of Eurasia would come to mark the southern and western boundaries of the empire, preventing it from expanding into South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Mediterranean, and the rest of Europe.

Growth of the Mongolian Empire. Genghis Khan died in 1227.

Growth of the Mongolian Empire. Genghis Khan died in 1227.

The Mongolian conquests would go down as one of the most destructive and transformative events in the history of civilization. Centuries, if not millennia, of cultural artifacts and technological infrastructure were destroyed, especially in Persia and Mesopotamia. Huge swaths of irrigation were taken out, likely causing massive famines. Entire cities were decimated, either out of retribution or to optimize the flow of goods across the Silk Road by eliminating less important and more inaccessible cities. So much urban landscape was returned to nature that some suggest a net reduction in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

At the same time, much of the technological and professional experience of the conquered societies was integrated into and distributed throughout the Mongolian empire. With the world connected like never before under a common law and administrative framework, the Silk Road was completely revitalized, enabling an explosion in the safe transport of ideas, technology, goods, and people across Eurasia. Rather than increase taxes, the Mongols chose to build wealth by encouraging and lubricating productive enterprise across the empire, transforming the Mongol rulers from warriors to shareholders.

Pax Mongolica

The Mongolian Peace, or Pax Mongolica, which followed the conquests, laid the foundation for modern society - a secular international law based on principles of commerce, open communication, knowledge sharing, and religious freedom operating at large.

Printing was adopted at a massive scale, and dramatically increased general literacy. Legal texts and government decisions were printed and disseminated, greatly improving access to the law. Books of all kinds and all languages proliferated, on agriculture, scriptures, law, history, medicine, mathematics, song, and more. The Mongols were in some sense the first successful universalists, pursuing the pragmatic over the ideological and shattering the prior monopolies on thought.

Paper currency was standardized, and a common unit of account could be used from China to Persia. Torture and punishment were reduced as methods of retribution, in favour of fines. Preference was made for more local dispute resolution. Minimum standards were set for professional knowledge and access to professional services was greatly enhanced. The Mongolian city of Karakorum, erected by Genghis Khan’s first successor, became the most religiously open and tolerant city in the world. The Mongols tread lightly on the conquered regions, imposing little of their own language and culture, of which they were actually quite protective.

All of this was in stark contrast to the more oppressive, exploitative, and discriminatory practices of Europe at the same time.

Europe, of course, would have the most to gain from the Pax Mongolica. While they mostly avoided falling under Mongolian rule, they received immense benefits from the technologies and values that filtered in across the Silk Road. Technologies like printing, gunpowder, and the compass, which would ignite the renaissance. Administrative advances like paper currencies and Islamic mathematics. At the dawn of the renaissance, encouraged by stories from travellers like Marco Polo, who spent time in the Mongolian court, Europe came to admire the Mongols, and even to revere Genghis Khan.

After unprecedented success in integrating Eurasia, the Mongolian Empire was ultimately destroyed by a pandemic of the Bubonic Plague, which seems to have arisen somewhere in East Asia in the 14th century and spread rapidly throughout the empire along trade routes. Entire regions were decimated and cut off from one another as the infrastructure of the empire collapsed and tens of millions of people died.

Reverberations

The story of the Mongolian Empire encompasses essential components in the mythology of history and holds many parallels for our current moment. Emerging due to topographical and climatic conditions during a warm spell in the Mongolian steppe around the 12th century, the nomadic warriors conquered civilizations as far as topography and climate would allow, rapidly integrating technology across the entire region and accelerating the evolution of culture. Driven by humanist and universalist ideals, the Mongols ended the era of self-sufficient city states and established globalized trade in a hyper-connected world of rich information flow across robust communication infrastructure. But this infrastructure was was ultimately the conduit for its own downfall at the hands of invisible enemy, an infectious parasite. Sound familiar?

And the cycles of history play on repeat.