Local Money Systems

As you may know, I’m quite enchanted with the idea of local money systems - money designed to facilitate local economic organization and trade. There’s a nice overview in Bernard Lietar’s Creating Wealth. I think they’re the best application of blockchain tech and the best hope for a sustainable civilization.

I expect that progress in blockchain tech and tokenomic primitives (like bonding curves) will revolutionize the field of Optimum Currency Areas and paint a path towards a more sustainable theory of international monetary economics grounded in self-sufficient local economies. At least this seems to me like the critical research project for economics this century. Perhaps MMT will even serve as a kind of precursor for this, though I suspect it will need to mature into something more “ecologically sound”.

In the meantime, this is a short note on some types of local money and their most promising economic function for businesses: liquidity saving.

Types of Local Money

The simplest local money is custodial. You give $100 to some trusted local organization, and they give you 100 LOCAL in return. You can spend the LOCAL in the community, or you can cash it back it in, but say for only 95 cents on the dollar. The idea is to keep the money circulating in the community. The money is backed by custodial reserves (dollars at the trusted org). Examples include BerkShares.

Another kind of local money is mutual credit. You join a cooperative of businesses that accept payments for goods and services in LOCAL on par with $. You take out a loan of 100 LOCAL (ie. 100 LOCAL are created and issued to you!), but you must commit to accept say 500 LOCAL (on par with $) in the future as payment for your goods or services. The money is backed by the mutual committment to accept it (on par with $) for goods and services, but is not redeemable for $. The best example of this is the WIR Bank in Switzerland, which started during the Great Depression, and is the longest running and largest local money system in the world. But see also Grassroots Economics, Sardex, and the many LETS.

Similar to mutual credit are time banks, but instead of pricing LOCAL in $, it’s priced in time.

Another kind of local money is trade credit clearing, also known as invoice or obligation clearing. You join a cooperative of businesses that do business with eachother. You owe money to some of your suppliers, who owe money to some of their suppliers, who owe money to you. Any closed loop of obligations like this (a “cycle”) can be netted out, reducing the overall amount anyone has to pay. While this doesn’t feel so much like money in an account, it is a liquidity saving mechanism - it reduces the amount of money you would otherwise need to settle your payments, functioning effectively as a kind of medium of exchange. Examples include the TCT system in Slovenia

Similar to invoice clearing are clearing houses. Instead of only netting out the cycles and leaving the remaining obligations in place between businesses, a clearing house serves as a central counterparty to net everyone against everyone else. Businesses with deficits pay the clearing house, and those with surpluses collect from it. Examples include many of the world’s central banks (which act as clearing houses for their commercial banks), as well as CHIPS, LCH, etc.

There are a number of other kinds of local money, but these seem to be the most popular. Notably, many custodial and time bank systems have ceased their operations due to overhead costs. This is perhaps not surprising, as these systems seem to lack a kind of scalability. That said, there seems to be renewed vigor and potential among mutual credit and credit clearing systems, which do appear much more scalable.

Liquidity Saving Mechanisms

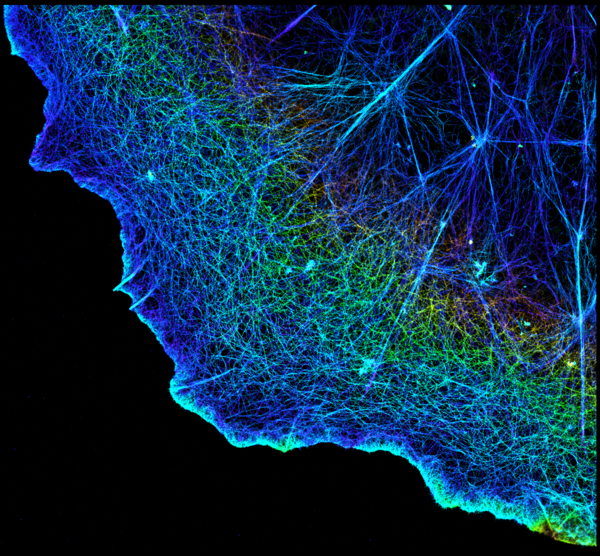

Earlier this year, a paper was published by Tomaz Fleischman et al. on Liquidity Saving Mechanisms - looking at both obligation clearing and mutual credit. The paper seemed to so illuminate the field of local money systems that a review was written called Someone Just Turned the Lights on. The paper analyzed data from two real world local money systems: a national trade credit clearing system in Slovenia, and a mutual credit system in Sardinia. The paper contains some incredible visualizations of the cyclic structures within the larger obligation graph, and of the liquidity profiles of firms with and without obligation-clearing.

Fleischman’s paper highlighted the major beneficial impact these systems have had on their respective economies, specifically in terms of the liquidity saved (ie. payment obligations reduced) by participating businesses. Hence the term, liquidity saving mechanisms. But it also showed through simulations how much more could be saved by combining the two mechanisms - namely, the combination of invoice clearing and mutual credit could save businesses up to 50% (!) of their liquidity needs! That’s huge.

As it turns out, liquidity savings mechanisms are a reasonably well studied concept in economics, though primarily in the context of financial institutions. Banks regularly use liquidity savings mechanisms (especially clearing houses) to reduce the need for payments to be settled with $, just by netting out participants against eachother. Banks do this every single day in clearing houses like CHIPS and the Federal Reserve itself, saving themselves on the order of trillions of dollars of liquidity per year. We need only to make these tools available to the general public. This is one of the promises of local money.