This is the introductory post in a series on the properties of money and the tensions between them.

It is perhaps inevitable that every philosopher of money will venture at some point into the muck of money’s notorious “properties”, trying to make space for some light. Unfortunately, many such ventures seem to result in obnoxious arguments as to why one or the other of the properties is the most important feature of money. We refuse to show the complex institution of money this level of disrespect. Instead we seek to honour each of the properties in their true glory.

The properties of money are most commonly stated as the Unit of Account (UoA), Medium of Exchange (MoE) and Store of Value (SoV).1 Typically, in the history of economic thought, the Medium of Exchange is taken as the most important, as economics is about exchange, and money is its means. But the credit and Chartalist schools of the early 20th century have experienced a renaissance in the last few decades (most popularly in the form of MMT), challenging the hegemony of the Medium of Exchange, and pronouncing in retribution the supremacy of the Unit of Account. Naturally, there are also those who worship the Store of Value, but they are more likely to be either gold bugs, crypto bros, rent-seeking sociopaths, or otherwise preoccupied with concern about the impending apocalypse - in any case, not considered polite company.

By over emphasizing the Medium of Exchange, and taking money merely as a convenience of barter, the mainstream tradition blinded itself to the temporal structure of exchange. They took what is fundamentally an asynchronous process, of two distinct obligations to deliver, and theorized it as a synchronous, simultaneous event. But one exchange is in reality two transfers. And between those transfers, no matter how close together they are, lies what we’d call a monetary debt - an obligation to pay something worth a monetary amount. The spot market is an institution where it’s possible to safely carry out these two transfers back to back, as if they were simultaneous. But they never really are.

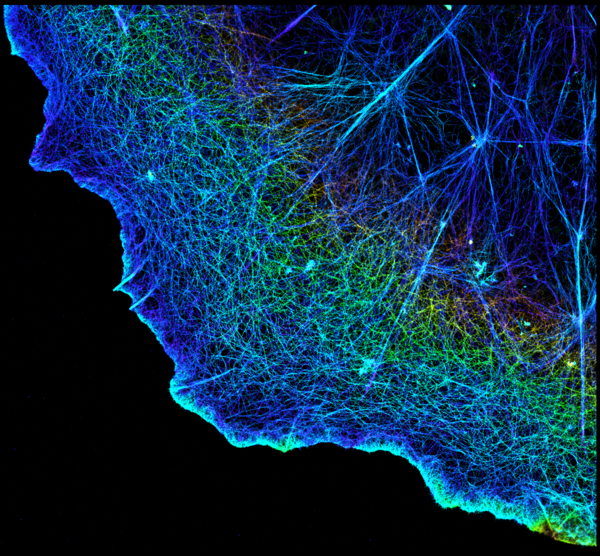

What the mainstream conception missed, despite it glaring at them in the form of sovereign faces on coins and bills, were problems of liquidity and legitimacy - of credit and its security, of the ability to roll over debts, and to settle payments when they’re due. By taking money as a neutral veil, these problems disappeared into blundering abstractions of the aggregate “supply” of a fictitious commodity called money, managed by all powerful central banks. But this is a gross obfuscation. Money is not some fictitious commodity, it is an evolving web of payment obligations engulfing the world economy. What matters is not the quantity of money, but its quality, and quality is defined by patterns in the payments network. For us, money is where the payments are.

Our position, at least for the sake of this series of posts, is that money has a more singular function, that of denominating and clearing debts, which is to say, requesting and receiving payments. Money is where the payments are.

Money as Settlement

Consider that money is an institution of settlement. By this we mean an institution that arranges for the coordinated reduction of uncertainty in a domain of experience. Other common institutions of settlement are war, marriage, and law (religious and secular), and in a sense these comprise the foundations for institutions of money. The institution of money specializes in settlements of a “monetary variety”, effectively, payments to settle debts. But it could also be said that the kind of money we use is itself a settlement between the various social strata on how value and wealth will flow through society, on how we replicate patterns of inequality over time.

Settlement is an apt word, since it also denotes the physical settlement of a group of people in a common area, agreeing to build their lives together in one location. Institutions of monetary settlement are also a reflection of how we agree to build our lives together.

With this framing in mind, of money as an institution for payments - for settling debts - we can think about the three properties of money as follows: the Unit of Account allows us to denominate debts; the Medium of Exchange allows us to settle those debts, here and now; and the Store of Value allows us to settle those debts, elsewhere or later.

That is, armed with the fiction of an accounting unit, we can denominate debts to one another (i.e. extend each other credit). Then, when a debt falls due, and the creditor expects to be repaid something with value equal to the originally denominated debt, the debtor can conjure a means of settling the debt here and now. And as a debtor, in order to ensure I can settle my debts in the future (in the same or even different Unit of Accounts!), I will seek a way to store value in the meantime so I can guarantee access to the relevant means when the need to settle my debts arises, wherever and whenever that might be.

Properties and Tensions

To summarize, we can consider the properties of money as follows:

- the Unit of Account is for denominating debts

- the Medium of Exchange is for clearing debts, here and now

- the Store of Value is for clearing debts, elsewhere or later

This is all relatively straight forward. But what we’d like to explore are the tensions that lie between each pair of properties.2 It is within these tensions, we suspect, that money finds its character, and that we might find a more complete understanding of how the global monetary order is failing, and what, if anything, we might be able to do about it.

In this series, we’ll consider a characterization of the tensions as follows. Between the Unit of Account and the Medium of Exchange lies a tension between elasticity and discipline, which gives rise to a problem of liquidity. Between the Medium of Exchange and the Store of Value lies a tension between “bad” and “good” money, which gives rise to a problem of legitimacy. And between the Store of Value and the Unit of Account lies a tension between deflation and inflation, which gives rise to a problem of solvency:

- UoA/MoE: liquidity - the tension between elasticity and discipline

- MoE/SoV: legitimacy - the tension between “bad” and “good” money

- SoV/UoA: solvency - the tension between deflation and inflation

These tensions are somewhat masked today by a homogenizing institutional structure in the global monetary order that conflates them within a single all powerful currency unit, the dollar. But such a totalizing monetary construction is unique in the history of monetary systems, which are characterized by a plurality of monetary forms and substances that unbundle the properties of money and bridge across different domains and scales of exchange.3 Even the dollar system has the properties of money effectively unbundled, where the Unit of Account is the USD, the Medium of Exchange is the eurodollar, and the Store of Value consists of US Treasury Securities. But by running our economies effectively blind to the underlying reality of these tensions, we have precipitated a perpetual crisis in the liquidity, legitimacy, and solvency of our monetary order. Surely this is something we need to understand. This series hopes to help.

Each of the posts that follow will explore one of these three properties of money, along with one of its tensions. First, we will look at the Unit of Account, the denominator of debts, and its tension with the Medium of Exchange, which yields the problem of liquidity. From there we will turn to the Medium of Exchange, the clearing wheel of the here and now, and to its tension with the Store of Value, a repressed battle over legitimacy. Finally, we will turn to the Store of Value, the guardian of debts to be cleared elsewhere or later, and its tension with the Unit of Account, which strikes as an existential question of solvency, of how we measure what we’re worth. Perhaps finally, or even throughout, we will discover something about sovereignty, about how we define who we even are.

This is our ambition anyways. Stay tuned.

-

Sometimes “means of payment” or “means of settling debt” are considered as a fourth property of money, but as we’ll see, we’d rather think of this as actually the key function which the standard 3 properties enable. Money isn’t about exchange, it’s about settling debt, which includes its denomination, transfer, and valuation. ↩︎

-

This characterization was inspired partially by Colin Drumm’s tweet and work, and by the Collaborative Finance team at Informal Systems. ↩︎

-

For a phenomenal review of money’s historical plurality, see Akinobu Kuroda’s A Global History of Money. For the story of how the properties of money ended up bundled together in what would become the Gold Standard and eventually our modern Dollar system, see Amato and Fantacci’s The End of Finance ↩︎