The velocity of money denotes a kind of circulating quality of money, an ability to flow. But it appears as a poorly understood, or largely ignored, phenomenon:

What does the "velocity" of money purport to capture, that mere spending does not?

— Joe Weisenthal (@TheStalwart) October 26, 2021

Velocity has a well-know definition: the ratio between the total spending in an economy and the money supply. But Joe is asking about what that ratio actually purports to capture. A number of the responses to that tweet suggest that velocity is a mere accounting fiction, something that falls out of the Equation of Exchange, rather than anything particularly meaningful unto itself. But focusing on a definition in terms of aggregates (total spending and money supply) both obscures and distracts from the underlying patterns of the monetary system. Money moves in different ways in different parts of the economy. No singular measure of velocity can adequately capture that heterogeneity. And yet, as a concept, velocity may still have something important to tell us.

The concept of velocity beckons us to look deeper at the structure of the payment system, the dynamic pattern of monetary relationships that compose the economy. Where does money begin, and how does it flow? Where does it flow to, and can it flow in cycles? Velocity reflects a kind of efficiency, an alchemical ability to do more (transactions) with less (money). A fresh look at velocity can help us understand how to move from our current patterns of unsustainable, exponential growth towards a more sustainable, circular growth economy. If we want to get serious about sustainability, then money supply, total spending, and even prices alone don’t tell us nearly enough - we need to dive deeper into money’s velocity.

Measuring Money

Velocity is defined most traditionally through the Equation of Exchange, as the ratio of total spending (over some period) to the total money supply:

Velocity = Total Spending / Money Supply

If there’s only $100 in an economy, and we want to do $5000 worth of transactions, then on average, every unit of money is going to be used 50 times - the velocity is 50. So we can think of velocity like a frequency - it’s the number of transactions each unit of money is used in. If there’s more spending than the total money supply, then units of money are being used multiple times.

Both total money supply and total spending are relatively straightforward to measure, and thus it’s easy to compute velocity from them. Money can be literally counted,1 and the total spending is the sum of the amounts spent in every individual transaction. But it’s more difficult to measure velocity directly. One could imagine trying to measure velocity by giving each coin or bank note a serial number, and recording it as part of each transaction, so you could see how many times a given coin was literally used, and then average over them. Of course some coins might not move at all (their owners are hoarding them), while others might move rapidly through a community with more active markets. So we can see that the velocity measure is an average over the tendency for money to circulate in an economy.

It’s less clear how to measure velocity directly in ledger-based or electronic systems, where there are no distinct monetary tokens like coins that can be tracked, but just balances in an account. There are still payments between accounts, of course, and we can still compute velocity as a ratio between total payments and total money supply. But now instead of dealing with literal circulation of physical tokens, velocity is some more abstract representation of patterns in the payment system. We’ll come back to this.

Another way to think about velocity is via its inverse. If velocity is a

frequency, then its inverse is a duration. If velocity is the number of

transactions a unit of money is used in over some period of time, its inverse is the duration of time a unit of money is

held, before it’s used in a transaction. This is basically liquidity demand, Liquidity Demand = 1 / Velocity.

Rearranging our original equation, we get Money Supply = Total Spending * Liquidity Demand, which tells us that the money supply is composed of two activities: spending and holding.2

Interrogating Inflation

The Equation of Exchange is often written as

MV = PQ

where M is the money supply, V is the velocity, and PQ is the total nominal spending,

composed of an index of prices (P) and an index of real output (Q). The equation

is itself a tautology. What is interesting is

whether it can tell us anything useful about reality.

This domain has been largely dominated by the Quantity Theory of Money,

which supposes that the Equation of Exchange provides a model of inflationary

processes in the world: given a fixed velocity and output level, more money means higher prices.

The Quantity Theory has a centuries old history, rooted in repeated observations that increases to the money supply (whether through debasement, an influx of precious metals, or the issuance of paper money) tended to increase prices broadly. It culminated ultimately in the hands of Milton Friedman, who catapulted it into a dominant economic religion: Monetarism. And the policies of our central banks today continue to reflect its legacy in their attempts to target inflation by manipulating the money supply.

The Quantity Theory of course has some truth to it. But it betrays a kind of naive simplicity that makes it hardly useful as a guide to a more complete monetary theory. For one, it says nothing about the dynamics of how money flows through the economy, and the effects it has as it flows. Increases in prices are not immediate, they happen at different rates throughout the economy, and disproportionately benefit those closer to money’s source.3 The Quantity Theory also assumes a neutrality to money that allows a clean separation between prices (“nominal value”) and output (“real value”). But money is no mere “neutral veil” layered over underlying “real” processes. Money is a dominant force in the productive organization of society; it is a factor of production itself.

And then there’s the matter of velocity, which adherents of the Quantity Theory generally take to be a constant. But we know that in times of crisis, velocity collapses (the demand for money sky-rockets). And with the surge in money supply over recent decades, measures of velocity appear to be falling everywhere. We don’t know if there’s such a thing as “the right” velocity, but low velocity seems like a kind of sickness in the payments graph.

The Knuts and Bolts of Payments

Velocity as commonly defined is simply the ratio between aggregate spending and the money supply. But over a hundred years ago, Knut Wicksell4 showed that any amount of money, even an infinitesimal amount, is in principle sufficient to clear all the transactions in an economy, assuming the velocity can be made arbitrarily high. For instance, in a closed economy, where I owe you $5 and you owe me $5, then even with only $1 of circulating money supply, we can completely pay off our dues by sending the $1 back and forth as many times as necessary (i.e. 10). Wicksell extends the example to a larger society, where payment obligations build up over a period, after which everyone assembles at a fair to send whatever amount of money exists back and forth until everyone’s debts are cleared. Of course, no economy (except the global one) is truly closed, and hosting such fairs would obviously be impractical, but the example emphasizes that velocity is somehow a measure of the connectedness of the payments graph, of the ability for money to flow through it, for a single unit of money to be used to clear many transactions.

Wicksell takes the example further by introducing a bank that everyone uses, and which issues credit (i.e. “deposits”) that can be used in place of money. In such a scenario, where there is effectively no money used for payments, as everyone uses bank credit instead, the velocity of money is found to be infinite (i.e. spending divided by 0)! Hence the apparently quantum nature of credit money:

right. velocity is when you have one dollar but if you push it through a slit into the economy it interferes with itself and creates two shadows on the other side of the economy

— Rohan Grey (@rohangrey) October 26, 2021

Of course today, we consider bank credit itself to be money, thus reinstating a non-zero denominator. But Wicksell’s example highlights that velocity is not just a derived ratio, but a reflection of the structural reality of the payments network. Bank deposits, for instance, are initially conceived as credit, a trick to increase the velocity of metal coins. But over time, bank deposits come to be considered money themselves. And so what was once an increase in velocity at one level of the hierarchy of money, over time can become an increase in the money supply at the level below. Thus the velocity of money reflects the evolution of money’s structure.

Historically, say in medieval England, when the circulating money supply consisted primarily of gold and silver coins, velocity was structurally constrained by the limited availability of small coins.5 The smallest coins were commonly larger than a day’s or even a week’s worth of transactions. And even if there were smaller denomination coins, the prohibitive cost of making them typically meant there weren’t enough. Thus, while the coins that did exist might have circulated with high velocity, certain kinds of spending that people would have liked to engage in were structurally restricted, since the denominations of currency simply did not exist to facilitate them. They would have to resort to barter, or to local credit relationships (running up tabs), which might provide some relief, but were still severely limited.

Fiat money and banking institutions would come to resolve this particular constraint on the payments system by moving us away from coins towards accounts, and through a couple centuries of inflation that have made the price of daily transactions much larger than the smallest units of money. Perhaps ironically, despite major improvements in the payment system, aggregate velocity appears to have actually fallen as we entered the modern period, as the increased monetization of society meant people increased their overall demand for money balances. But even still, certain transactions remain infeasible, like so-called “micro transactions”, a structural constraint that stems from the virtual impossibility of sending high volumes of small transactions in the current configuration of the payments system. And this constraint appears to pose a serious impediment to alternative, and perhaps more responsible, commercialization strategies for digital IP. So velocity, at least its structural determinants, seems to matter.

Clearing The Way

What other structural constraints might there be in the modern payments system? Consider how payment obligations come about in the natural course of doing business. Each firm builds up a mix of accounts receivable (“AR”) and accounts payable (“AP”) with the various other entities it engages with. When a firm is calculating its own solvency, the AR counts as an asset (“money owed to you”) and the AP counts as a liability (“money you owe”), so they can be offset against each other. But a firm cannot actually clear its AP using its AR, because the receivables (AR) aren’t actually money - they’re not broadly accepted media of exchange that can be used to make payments, they’re just the IOUs of some entities that owe you money. In order to clear its AP, the firm needs actual money, which might only be possible if it can collect on its AR. This is the problem of “liquidity”, or the “survival constraint”, faced by every economic actor every day. The survival constraint creates demand for money in order that each economic agent can meet its payment obligations as they fall due. This is the heart of Perry Mehrling’s Money View - you can be insolvent for a while, but “liquidity kills you quick.”

The liquidity constraint is a structural constraint on velocity. It derives from the gap between genuine money and any old entity’s IOU, which is effectively the structure of the payment system. Banks are fortunate enough in that their IOUs are broadly considered money by the rest of us. But even between banks, where payments are made in bank reserves (or historically, in gold), they seek to relieve the liquidity constraint by maximizing velocity (read, “efficiency”) of payments between themselves, making use of as little monetary reserves to support as large a volume of payments as possible. Of course, even banks can fall victim to the survival constraint, as the historic events of 2008 demonstrated.

The banks have access to extremely high velocity structures within their payments network, clearing houses that save them trillions in payments. In a clearing house, at the end of each day, all interbank payment obligations are netted out, and every bank makes a small payment to, or receives a small payment from, the clearing house. Doing so allows them to effectively settle much of their accounts payable with their accounts receivable. But what about the rest of us? Can we do something similar for businesses in general?

In the earlier example from Wicksell, we sent whatever money we had back and forth to clear all the payments. And in the example of banks, they establish a clearing house so each bank only pays or receives from the clearing house; this changes the graph of counterparties, so instead of owing each other, each bank only owes (or is owed by) the clearing house. But there’s another approach, which does not require sending money around, and does not require changing the graph of counterparties (who owes who), but rather looks at the structure of the accounts payable graph itself, and clears any cycles that exist within it. If I owe you $5 and you owe Abed $5 and Abed owes me $5, we can clear all three transactions without using any money at all. And if I owed you $6, we can still clear $5 off all payments, without changing the graph of counterparties, but only reducing the amount everyone owes each other. This is the magic of credit clearing.

The Circle of Life

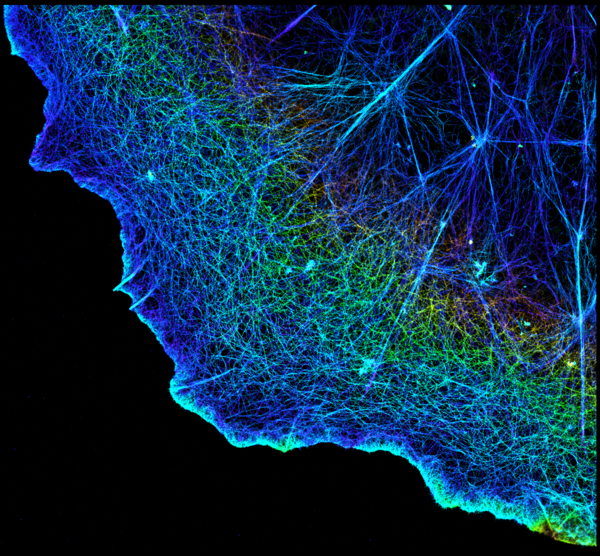

Credit clearing is based on circular patterns within the payments graph. When one firm’s output is another firm’s input, and so on, in a circle. This pattern of cyclical flow is at the heart of all healthy ecological systems - the great circle of life. And it exists all through out the economy, constituting a self-sustaining core of economic activity. Circular economics is a thriving movement.

But this core is totally ignored by, and even invisible to, the modern economic and monetary system. We don’t know if its growing or shrinking, or what percentage of total economic activity it comprises.6 And many of our economic habits appear directly opposed to it, like the obsession with exponential, non-renewable growth. But as a self-sustaining core, these cycles represent an economy’s robustness, its ability to withstand and respond to shocks. And by looking at the pattern of payment obligations, we can surface this core, and nurture it, suggesting a new, more sustainable approach to economic growth and resilient economies that integrates directly with the monetary system.7

We can think about this in terms of the Equation of Exchange, MV = PQ.

If we want economic growth (increased output, Q), then we will need a greater money supply (M),

greater velocity (V), lower prices (P), or some combination thereof. Much of the economic growth associated with

technological innovation appears as lower prices. But deflation in the general

price level (and especially in wages) has its own host of problems, and we have been targeting for

decades a positive inflation rate.8 Hence, much of the accommodation for economic

growth seems to come from increases in the money supply, primarily in the form of

bank loans.9 But what if instead we could enable economic growth by increasing

velocity?

This is the idea behind credit clearing. By identifying closed loops of payment obligations in the economy, we can clear them without the use of any money at all. Each cleared cycle is thus a localized increase in velocity. But collectively they comprise a major improvement in the resiliency of the economy as they can significantly reduce the liquidity constraint on every agent that participates in a clearing cycle.

These cycles of economic activity suggest a more sustainable approach to economic growth. Rather than the current model of unsustainable exponential growth in spending, we can instead orient around more sustainable growth in velocity.10 This still allows us to grow, but does so in a way that each component of growth derives from a sustainable loop, rather than a turbulent vortex. We can move from a linear economy to a circular one.

The parallels between the flow of money in an economy and the flow of energy in ecology run deep. It is well understood in ecology that what matters is not so much the total energy in a system (say, the “money supply”), nor the total metabolic activity of the system (the “total spending”), nor even the temperature (the “price level”). What matters are the patterns of energy flow - effectively, the food web. Sustainable systems are those that are able to effectively store up energy within their internal structure by channeling it through closed loops.11 And this is what we should be trying to capture by looking at velocity.

-

Not to imply that actually measuring the money supply today is easy. In the US, for instance, most of the dollars are created off-shore in the form of “eurodollars”, which the Federal Reserve does not know how to measure. ↩︎

-

Some people argue that money doesn’t actually flow, it is only ever held, punctuated by moments where one person takes over holding money from another (i.e. payments). And for this reason they might prefer to think in terms of demand for money, rather than its inverse (velocity). A lot of foundational thinking in early 20th century monetary theory (e.g. both Keynes and Mises), was based around a fresh look at the demand for money. But while demand focuses attention on acts of saving, velocity, as we’ll see, encourages us to look at the broader payments network. ↩︎

-

This is the well known Cantillon Effect, after Richard Cantillon, the mysterious 18th century economist and banker whose short “Essay on The Nature of Trade in General” played a major role in the birth of political economics. ↩︎

-

Knut Wicksell was a Swedish economist who made major contributions to monetary theory, especially the theory of interest rates. His work was highly influential on monetary economists in the early 20th century, including both Mises and Keynes. The examples here are taken from his 1898 “Interest and Prices” ↩︎

-

See Christine Desan’s “Making Money” for a detailed historical account of the challenges of maintaining the monetary system in medieval and early-modern England. Desan’s account heavily cites Sargent and Velde’s “The Big Problem of Small Change”. See also George Selgin’s “Good Money”, which tells the story of how private industry solved the small change problem for itself by taking minting matters into its own hands. ↩︎

-

Researchers have begun to get access to and analyze this data where it exists, for instance in the national credit clearing system in Slovenia, and in Sardex, the mutual credit system in Sardinia, Italy. See Liquidity-Saving through Obligation-Clearing and Mutual Credit. ↩︎

-

Central Banks are currently captured by a paradigm of systemic risk. They may be able to transition to a more sustainable model by better support for more local and cooperative forms of credit clearing and credit creation, directly between businesses. I suspect blockchain technology can play a major role in facilitating this. But that’s a topic for another post. For some preliminary ideas, see my critique of MMT. ↩︎

-

There is growing support for “NGDP targeting”, where Central Banks target total nominal spending directly, rather than the price level, allowing the price level to adjust for genuine gains in productivity. ↩︎

-

The vast majority of money in the world is created endogenously by commercial banks through the issuing of loans. This is the monetary engine of economic growth. But ever since 2008, this engine has collapsed. Central banks have attempted to compensate using their own balance sheets and Quantitative Easing, but the “money” they thus create (bank reserves) is no substitute for the money created by commercial banks (primarily, “eurodollars”). There is thus a kind of permanent deflationary “potential” in the global monetary system since 2008 throttling both inflation and economic growth. See, for instance, Jeffrey Snider on the topic. Introducing credit clearing systems to support the liquidity of small businesses might help combat this, by enabling higher velocity payments to compensate for the lack of money supply. ↩︎

-

This might be considered a refreshed version of the classical “real bills” doctrine, which suggested that credit expansion was not inflationary so long as it was short term and self-liquidating - meaning, short-term bills of exchange supporting real commercial activity. Real bills doctrine struggled to bridge the gap between the short-term money market and the needs of longer-term capital financing, and was eventually abandoned. But the focus in the real-bills doctrine on the quality of collateral in the money market is sometimes considered a kind of “Quality Theory of Money”, in contrast to the “Quantity Theory”. Where the Quantity Theory is focused on money and prices, a Quality Theory might provide a renewed look at velocity and spending. As economics became increasingly obsessed with being a science in the 20th century, it largely lost the “art” of banking, and with it, the evaluation of money’s quality. If we are to fix money and banking, this art must be restored. ↩︎

-

See, for instance, theoretical ecologist Robert Ulanowicz’s concept of Ascendency, which uses information theory to captures the resilience of an ecosystem. In “Life and the production of entropy”, Ulanowicz borrows the “discount rate” concept from economics to describe the residence time of energy in biological systems and its relation to succession and sustainability. Analogous concepts of ascendency and residence time ought to be developed for economics and the payments network. See also Mae Wan Ho’s The Rainbow and the Worm, mainly Chapter 7, “Sustainable Systems as Organisms”, as well as my blog post, Economic Organisms, and my talk, Stakeholders and Statemachines. ↩︎