Last year I read F.A. Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom and Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation back to back. Both published in 1944, these great works of political economics were attempts by their authors to grapple with the collapse of western civilization into the fascist totalitarianism of the Second World War. For Hayek, a classical liberal, totalitarian tragedy follows inevitably from the authoritarianism of State Socialism. For Polanyi, who was more of an economic sociologist, the fascism of WWII followed inevitably from the dehumanizing forces of the preceding century of Market Capitalism. On the surface, the two views seem diametrically opposed. But they may have more in common than meets the eye. At a deeper level, they share a kind of information theoretic concern about the ability of the economy to represent the natural and social world in which it is embedded. Perhaps it is actually the failure of this representation mechanism that causes us to lapse into the totalitarian.

For Hayek, that information theoretic concern is the limited capacity of centralized decision-making in complex economies. In this view, markets are an evolutionary medium that enables spontaneous order to emerge. Hayek argues in favour of decentralized decision-making in competitive markets, regulated by slowly evolving institutions with strong Rule of Law that inhibit monopolization and foster competition. This means generally applicable rules that are easy to understand and reason about, permitting individuals the freedom to plan for themselves.

For Polanyi, the information theoretic concern is the limited capacity of market-based systems to represent more substantive patterns of natural and social organization. His book is an epic history of the Great Transformation that took place over the course of the industrial revolution, where land, labour, and money were transformed from their natural and social reality into mere economic commodities, and all of society became violently subjected to the cold, calculating, artificial logic of a global, self-regulating, Market System.

Curiously, despite their allegedly opposing political views, there are a number of biographical threads that tie Hayek and Polanyi together. Both were born in late 19th century Vienna (Hayek in 1899, Polanyi in 1886). Both served for the Austro-Hungarian Empire in WWI. Both received doctorates in Law (Hayek from Vienna, Polanyi from Budapest). Both were associated with Jewish intellectuals (Polanyi actually was Jewish, Hayek merely suspected of being so). Both came from families of high intellectual achievement. Polanyi’s younger brother Michael was a noted polymath, and actually corresponded fruitfully with Hayek for years on liberty and spontaneous order. Hayek was second-cousins with Wittgenstein, whom he greatly admired, and his grandfather was a close friend of Bohm-Bawerk (co-founder of Austrian Economics). Both Hayek and Polanyi participated in the Socialist Calculation Debate of the 1920s, and both fled to London in the early 1930s. Polanyi’s daughter, herself an economist, even studied under Hayek at the London School of Economics!

Hayek and Polanyi represent in some sense the culmination of the two grand schools of central European economics - Hayek and the Austrian School, Polanyi and the Historical School. These schools have been dueling in the notorious Methodenstreit (“dispute over methods”) since the 1880s. Though there are many notable cross-overs and linkages between them over time (Max Weber, Joseph Schumpeter, etc.), the vitriol of past divides lingers on today in crude conceptions of political camps. And in the zoo of heterodox schools, the Austrian tradition appears like a Right-wing island in a Leftist sea. But in a way, both Hayek and Polanyi seem to transcend a crude Left vs. Right dichotomy through a more “localist” predilection, and through complementary information theoretic concerns about the ability of institutions to represent society. It is this complementarity between them that this post aims to elucidate by exploring their perspectives on socialism, markets, and societal institutions, as expressed in their respective books, The Road to Serfdom and The Great Transformation.

Socialism

Socialism means a lot of things to a lot of people, and meant different things to both authors. Confusion in the meaning of “socialism” appears to be at the heart of a great deal of strife between people. So it’s worth trying to clear things up.

The socialism Hayek attacks is what might be called State Socialism. This is the explicitly monopolistic thread of socialism that runs from the French tradition of Saint-Simon, through the German tradition of Marx, and on into the German Historical School, advocating for a kind of technocratic management of society. Hayek contends that this line of thinking is an “abuse of reason,” where the methods of the natural sciences are inappropriately applied to social problems, resulting in arrogant technocrats, dangerous scientism, and a kind of Monopoly Capitalism. The Road To Serfdom is itself part of a larger project that Hayek called the “Abuse of Reason” project, where he traced out the nature of this abuse more broadly.

For Hayek, society and economy are too complex to be comprehensively understood and directed by limited rationality; the true science of economy is more akin to the complexity theory of ecology than to the calculus or empiricism of Newtonian physics. Accordingly, there are fundamental limits to the ability of centralized decision-making to competently direct society. Policy which centralizes decision-making thus runs the risk of fostering dangerous monopolies. There is much evidence to support this, and he documents how technocracy led to totalitarianism on the Left and the Right - both the tragedies of Marxism in the Soviet Union and Nazism in Germany share this common intellectual tradition. A number of non-totalitarian but still fatal examples of top-down management of society by “experts” are especially well captured in James Scott’s Seeing Like A State 1.

Polanyi, for his part, is no advocate of State Socialism. He could even be said to agree with the general thrust of Hayek’s argument, which is itself an extension of the Socialist Calculation Debate ignited by Mises, Hayek’s mentor, in the 1920s. Mises argued that State Socialism, in the absence of market prices, could not perform the calculations necessary to organize complex production. Polanyi contributed to the debate with his paper, “Socialist Accounting,” where he agreed with Mises, but argued that Market Capitalism could not perform the calculations either, because it could not sufficiently account for environmental and social costs. Polanyi thus proposed a model consisting of multi-scale cooperatives to organize production. Mises responded that such proposals are better understood as “syndicalism.” For Mises, socialism meant only Marxist State Socialism.

Polanyi’s socialism follows primarily in the tradition of Robert Owen, who founded the cooperative movement in the early 19th century. Owen’s business in New Lanark, Scotland, which piloted early cooperative principles, was widely celebrated across Europe as the primary example of productive industrial organization that respected both its workers and the environment. Though Owen is considered today to be one of the intellectual founders of socialist thinking (along with at least Marx and Saint-Simon), his ideas, and the cooperative movement he founded, appear significantly under represented in the larger political economic debate. Owen’s line of socialism is not even mentioned in Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom 2.

Following Owen, the role of the state for Polanyi is not to organize or direct society, but rather to help avert harm. Hayek expresses a not too dissimilar sentiment, when he advocates a role for the state in regulating production for protective purposes, for instance to restrict the use of poisons, or limit working hours. But while Hayek might leave production to be organized by an abstract entrepreneur, Polanyi and Owen emphasize the importance of small, local cooperative organizations, that respect the workers and their environment, as the primary institutional form to organize around.

But socialism is something still more general for Polanyi. It is a recognition of the embeddedness of economy in society, an understanding that economic activity is always embedded within a larger social body. It is a rejection of the notion of economics as a somehow distinct, and more scientific, discipline from politics or sociology. This, in principle, would seem to resonate with Hayek’s rejection of economic scientism. But Polanyi further emphasizes the distinction between formalist and substantivist economic models - the formalist being concerned with rational decision-making under conditions of scarcity, the substantivist with a more organic study of how humans sustain themselves in their social and natural environments. And in this sense, despite rejecting the abuse of reason in mainstream, formalist economic models, Hayek is certainly more of a formalist. But it is in the substantivist model where other pro-social forces and patterns of organization, beyond simply market competition, play a critical role in the organization of society.

The Great Transformation is the tale of how the economy became dis-embedded from society. It describes how the new Market Society was constructed deliberately as a legal fiction by the State, and how the social body reacted in response. Polanyi referred to this alternation as the “double movement,” where (1) deliberate action to implement formalist economic ideas in law would cause the economy to be further dis-embedded from society, resulting in (2) spontaneous counter-movements by the social body to protect itself by attempting to re-embed economics in society. He gives a number of examples of this pattern as it occurred across Europe. Socialism in this sense is a kind of spontaneous response of the substantive society to the dislocating effects of forced formalist economic ideals. Polanyi sees much of the 19th century as a history of society trying to protect itself from the violent dislocations wrought by the industrial revolution - its satanic mills, slums, and proliferation of the poor. Thus Polanyi quipped: “laissez-faire was planned; planning, was not.”

Markets

Given the fundamental limits set out on the centralized direction of social processes, the market for Hayek is a decentralized mechanism that seeks to make as much use as possible of the spontaneous, distributed forces of society, and as little use as possible of coercion. This is the essence of Hayek’s liberalism. It builds on the fundamental revolution of the Enlightenment - the prerogative for individuals to think for themselves - by leveraging the forces of competition to make the best possible use of the heterogeneous information distributed across individuals in society - their preferences, understandings, proximities, and discoveries. Hayek thus sees any restriction on this basic competitive mechanism - in particular, the monopolies engendered by State intervention - as a grave threat.

Polanyi, in contrast, cautions that not all spontaneous change is good. In his view, the 19th century philosophy of liberalism largely disregards political science and statecraft. Polanyi argues that fast, undirected change needs to be slowed, where possible, to safeguard community welfare. Hence the importance of the rate of change of institutions within society, and not just their direction. But these views are not incompatible. The spontaneity Hayek seeks to leverage emerges within a particular institutional system. The spontaneity Polanyi seeks to restrain is that which evolves the institutional system itself. Notably, Hayek makes a similar argument about the need for institutional change to occur slowly. Both authors express a kind of respect for traditional institutions that emphasizes the “arational” information contained within them, and the need for a slow rate of change to enable the social body to adapt and respond appropriately.

Hayek is no adherent to a naive laissez-faire idealism. He critiques the laissez-fair ideologues repeatedly. Competition depends on sound institutions of money, markets, and information channels, not all of which can be adequately provided by the private sector itself3. As a result, Hayek argues that there is an essential role for government and the legal system in the deliberate creation of fair and robust institutions in which competitive forces can be effectively put to work. Notably, Hayek does not consider competition to be incompatible with an extensive system of social services, or of regulations that protect the basic rights of humans and nature, so long as they don’t foster the creation of monopolies or otherwise make competition ineffective. In effect, goverments ought to nurture the positive and regulate the negative externalities of market forces.

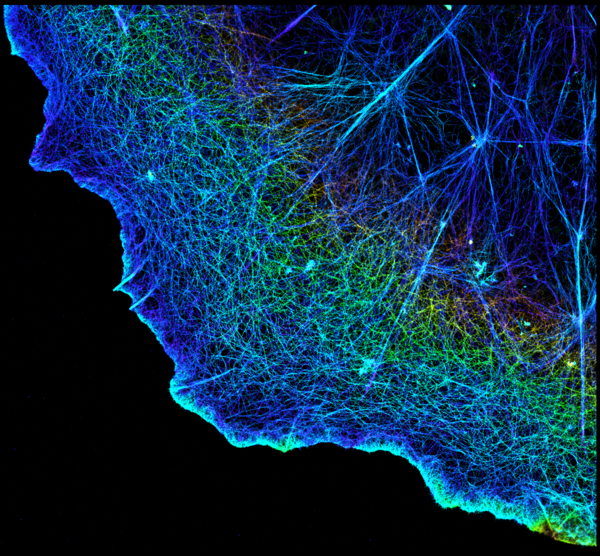

Hayek conceives of the market as a kind of distributed organism, a vast information network that can adapt and respond effectively to changes in the environment4. Intervention into the workings of this organism, through monopoly-inducing regulatory activity, is like a cancer, a permanent wound that handicaps the organism’s natural abilities and forces it to re-orient around an artificial disruption. But while Hayek emphasizes the critical importance of local decision-making within the market organism, he seems to have a kind of naive internationalism about markets, saying little about the locality, and the boundaries, of the organism itself. For this, we must turn to Polanyi. In a very real sense, life, and sustainable systems in general, are defined by their relationship to their boundaries.

Polanyi highlights that historically, markets and the forces of trade have always been socially embedded. Basically up until the time of Adam Smith, there were two distinct kinds of market: the well regulated local markets contained within towns (the virtues of which Smith celebrates), and the long distance markets of traveling traders. While Smith (and the Physiocrats before him) began to demonstrate the power of the principle of individual gain in organizing socially beneficial results, the institutions of their time were still embedded among other patterns of social organization. As Polanyi shows, the construction of nation states starting near the end of the 18th century obliterated the boundaries of previously localized and embedded market structures. What were once relatively self-contained market towns became subsumed into homogenized, countrywide national markets, which were linked up via the international gold standard into the global Market Society. Suddenly, individuals were placed in competition with the entire nation, or even the entire world, rather than a select group of producers in their community, with whom they often had longstanding non-economic relationships.

The new nationalized markets ignored distinctions between town and countryside, between the various towns and provinces. What was once locally regulated by the towns in their particularist way, now had to be regulated by the much larger states in a more generic fashion. And with that new scale came a host of challenges. It is curious that Hayek does not apply his own arguments of the scale-based limitations on knowledge to the same such limitations on the scale of the market institutions themselves.

This “liberalization” of markets across the country and the world was a relatively rapid and deliberate process undertaken by States, leading to widescale dislocations of the social fabric and the destruction of tremendous amounts of local institutional knowledge and structure. One might suspect that Hayek himself would disapprove of such rapid institutional change, even if it is towards the kind of liberal Market Society he advocated for. But this was the very process of the construction of Market Society - the transformation of the market pattern from well-regulated, socially embedded, sites of exchange to self-regulating masters of society built on a novel principle of individual gain.

The result of this transformation has of course been the rapid unfolding of untold miracles of production and a great advancement in industry and living standards. But it has also set us on a deeply unsustainable path towards destruction of the environment, and possibly of our souls, that we are reckoning deeply with now, nearly 200 years later. Hayek might argue that the true market system was never fully tried, due to decades of monopolistic intervention by States, and that many of our problems are the result of this intervention. And there is likely some truth to this. But Polanyi would counter that the pure Market System is itself a fiction, which applies the market pattern to aspects of the world which are not themselves truly marketable, like Land and Labour. That is, while the market pattern may apply appropriately to commodities, it can not be so indiscriminately applied to the factors of production themselves, which are not inherently produced for sale on the market, but constitute the environmental, social, and productive reality of society itself! Consequently, what Hayek would denote as unwarranted socialist intervention, Polanyi would posit as the natural and spontaneous reaction in the double-movement of society to dislocations caused by misapplication of market forces to social realities. Just as Hayek alleges that the State Socialists abuse reason by pursuing social science through the inappropriate application of the natural sciences, one might consider that Hayek is abusing reason in his own way by the inappropriate application of the market pattern of commodities to the non-commodity factors of production.

Polanyi offers some helpful concepts to understand this inappropriate application of markets, and relatedly, where the information-theoretic capacity of dis-embedded economics fail. The first is fictitious commodification. Polanyi refers to Land, Labour, and Money as the “fictitious commodities,” for they are not by their nature produced for sale on the market, and yet we treat them, in our theories and our institutions, like they are. Land, for instance, constitutes the entire natural world of ecosystems and geological forces, our great inheritance from the eons of physical and biological evolution in the Cosmos. Labour is the very capacity for human beings to actively engage in the world; it is our animating force. And Money constitutes the networks of production, exchange, and redistribution - it is the symbolic expression of large scale productive organization itself. The construction of the Market Society is synonymous with this fictitious commodification. Money came to be commoditized in the 17th and 18th century as central banks were established to manage a newly emergent gold standard. Commodification of Land picked up significantly in the 18th century with the enclosure movement. And finally, Labour was commodified by the middle of the 19th century with the establishment of a proper labour market in England in the Poor Law Amendment of 1834. This collective transformation destroyed existing patterns of local organization and the information contained therein by suddenly exposing and subjugating the entire apparatus of society to the international market. In effect, economics was torn from the bosom of society and made its master.

Second is Polanyi’s conception of the various principles of economic behaviour and their associated patterns. We have been talking largely of the principle of “truck, barter, and exchange” (“exchange” for short), and its associated pattern of markets. But Polanyi highlights three other principles and patterns, which dominated much, if not all, of life up until the 19th century, and which can still be found dominant today in the behaviour of families, friend groups, organizations, communities, indigenous tribes, and in various secondary ways throughout our major institutions. The set of principles and their associated patterns of organization are summarized in the table below:

| Principle | Pattern |

|---|---|

| Reciprocity | Symmetry |

| Redistribution | Centralization |

| House-Holding | Self-Sufficiency |

| Exchange | Market |

Each principle is a critical element of economic behaviour. In some sense, each builds progressively on those before. We can imagine the history of civilization as one moving from (1) the basic reciprocal relations between small human groups, towards (2) the more centralized states that facilitated redistribution of productive output to (3) nurture families in their house-holding as they aimed to provide their own sufficiency complemented by (4) markets facilitating the exchange of specialized output. In the economics and institutions that emerged in the 19th century with the Market Society, the market pattern and its principle of exchange were elevated, almost without consideration, above all others.

Today, modern economics is still largely blind to the other more substantivist principles, seeing only that of exchange, and a crude form of redistribution that is its understanding of the role of the state. But we must leverage all of these principles and patterns in our institutional arrangements, and respect their hierarchy, to adequately represent our natural and social environments. The market pattern may be necessary, but it is fundamentally insufficient. We need more in order to build sufficient representational capacity into the institutions of our complex society.

Societal Institutions

For Hayek, the great tragedy of much socialist thought is that it inevitably devours itself. Predicated on a presumption that reason is supreme, that it can be used to rationally organize society, that the technocrats can fully understand and direct the social body, it misconceives the process by which reason itself develops and evolves: differences in the knowledge and views of individuals. Hayek’s individualism is thus an “attitude of humility before this social process,” a “tolerance to other opinions.” It is the “exact opposite of that intellectual hubris which is at the root of the demand for comprehensive direction of the social process.”

Hayek warns about the limits faced by democracies in their efforts to plan and regulate society. Pursuit of the common good or the general welfare is only possible in areas where there is legitimate agreement on the scale of values and what should be done. But in many cases, such planning would require more agreement than actually exists in society. This puts it at grave risk of falling prey to a tyranny of the minority, of the largest group able to agree. And since democracy has worked best in fields where agreement can be achieved by free discussion, the merits of Liberalism can be understood as reducing the number of subjects on which agreement is necessary towards those for which agreement is likely to exist in a society of free individuals. In this sense, democracy is only possible in a liberal society.

Hayek stresses the importance of the Rule of Law - fixed, long-term, general purpose rules that do not favour particular groups or people but can be used by anyone to predict the behaviour of others and to collaborate in unplanned ways. This is in contrast to arbitrary discretionary power often exercised by governments to favor one group or another, which inevitably interferes with and complicates the plans of everyone else. If an issue cannot be regulated by general rules, and yet power to regulate it exists, then that power must be arbitrary. He argues that the application of the law without exception may be even more important than the actual particulars of what the law says (the Medium is the Message!), emphasizing the utility of the Rule of Law as an instrument for reducing uncertainty about the world and enabling individuals to more effectively plan for, and look after, themselves.

At a basic level of individualism, Polanyi agreed: “the right to non conformity must be institutionally protected. The individual must be free to follow his conscience without fear of the powers … entrusted with administrative tasks in … social life.” But he asserts that the kind of pure Market Society so cherished by the liberal ideology is itself an artificial ideal. The path-dependent, necessarily historical trajectory towards its implementation is so destructive to existing institutional patterns of organization in society as to necessitate regulatory reactions. This is the double-movement. And thus, given the mess that idealized Market Society has created for us, through its artificial commodification of the factors of production, we have no choice but to continually leverage the regulatory apparatus to get us out. And yet, Polanyi is clear on the need to preserve as much as we can from the inherently liberating ideals of the Market Society, its heritage in the Renaissance and the Reformation, and the freedom associated with the respect for each individual’s capacity to think for themselves.

Polanyi isn’t particularly prescriptive in the Great Transformation. Some allege that he displays a kind of romanticism for the feudalistic and tribal societies of the past (see for instance Rothbard’s scathing review, which deserves its own dedicated response). But the respect Polanyi has for these traditions isn’t in the way they oppressed or tyrannized, but in their holism. People may generally have been hungry and poor, but in the absence of major agricultural crises, they didn’t starve as a matter of general economic reality. Contrast this with the way the unemployed poor starved once the labour market was properly liberalized in the early 19th century, and a new kind of poverty exploded. It is this embedding that Polanyi is after. There is a sense that for Polanyi, these tribal and feudal orders are proto-cooperative - though they seethe with oppressive power dynamics, they constitute an integrated whole that seeks the basic sustenance of the complete unit.

Polanyi’s celebration of Owen’s cooperative movement provides some further insight. Owenism was exceedingly practical and un-intellectualized. It sought to engage productively in industrial society without sacrificing the holistic nature of the human being. It spawned the first producer’s cooperatives which sought to relieve the poor through a more integrated approach to market economy. Institutions of labour exchange and labour-backed currencies sprang up to empower the working and productive classes. Much of the impetus for these kinds of producer cooperatives would wane considerably over time, narrowing into the consumer cooperative movement. Polanyi considers this loss to be “the greatest single defeat of spiritual forces in the history of industrial England.”

And yet, in some sense, that cooperative impetus emerges renewed today. The work of both Hayek and Polanyi would inspire a more institutional school of economic thought that would bring the inherently cooperative nature of economy back to the forefront. From Polanyi flowered a renewed discipline of economic sociology. And from Hayek flowed the institutional economics of James Buchanan and Oliver Williamson, which would culminate in the work of Elinor Ostrom and her husband Vincent, on community-based governance and self-regulating civil society 5. The polycentric governance of the Ostroms harkens back to that of Polanyi’s nested cooperatives6. And in such models, in the synthesis of ideas from the Right and the Left, the Deductive and the Dialectical, the formalist and the substantivist - ultimately, in a proper reckoning with the ability of institutional structures to represent the nature of reality - we might find the basis for a sustainable society.

Special thanks to Jackie Brown for masterful help in editing this

-

Brad Delong, who describes himself as “no Austrian–I am a liberal Keynesian and a social democrat,” praised both the book and its intellectual legacy in Hayek, and criticized the book for insufficiently acknowledging its debt to Hayek. See his review of Seeing Like A State ↩︎

-

Marx and Engels would dismiss many of the socialist thinkers that came before them, including Owen, Proudhon, Saint-Simon, etc., as “Utopian Socialists,” to contrast them with the kind of “Scientific” socialism Marx and Engels were developing. In practice, the revolutionary bent of Marxist socialism would make it far more Utopian than the more grounded and practical approach of, for instance, Robert Owen. ↩︎

-

Later in his life, Hayek would publish “The Denationalization of Money,” where he explored the provision of money by the private sector, a school of thought that would inspire Bitcoin and the cryptocurrency movement. ↩︎

-

Hayek would expound this conception in his 1945 article, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” which would inspire the discipline of Information Economics. ↩︎

-

Elinor and Vincent founded the Bloomington School of Political Economy. Elinor won the Nobel Prize in Economics for her work on community governance of the commons. She shared the prize with Oliver Williamson, for his work on the nature of firms. Elinor Ostrom wrote a paper honoring James Buchanan and the influence of his work on her research. ↩︎

-

Coincidentally, the term “polycentrism” was actually coined by Karl Polanyi’s brother, Michael Polanyi, in his 1951 book, “The Logic of Liberty.” See “Polycentricity: From Polanyi to Ostrom, and Beyond.” As noted, Michael Polanyi and Hayek had a fruitful correspondence on related issues. ↩︎