Table of Contents:

- Introduction - Tesla vs. Bitcoin

- Green Tech - The Problem with Tesla

- Orange Money - The Promise of Bitcoin

- The Root of All Evil - Monetary Institutions and Political Economy

- In Proof We Trust - Proof of Work and International Trust

- Mind the Miners - Mining Is Not As Bad As You Think

- Big Bad Blockchains - What about Proof of Stake?

Introduction

Earlier this year, Tesla purchased $1.5B worth of BTC to hold on its balance sheet. This seems to have made a lot of people angry, or at least confused, including Elon Musk himself. Tesla, a bastion of our clean energy future, is helping us transition from fossil fuels to electricity. Bitcoin, a speculative digital asset, is using more energy than Switzerland and is (or at least was!) largely powered by dirty coal mined in China. What gives?

At the time, I suggested that Bitcoin might actually be better for the environment than Tesla. On the surface, this seems absurd. But our world and socioeconomy is a complex and dynamic place. Our environmental impact cannot be denominated purely in carbon emissions. Yes, we need cleaner sources of energy. Obviously. But we’ve also grounded our economics in obscene assumptions about indefinite exponential growth on a finite planet. Simply adopting a cleaner source of energy doesn’t actually help us there. We still consume and dispose of all kinds of materials at unsustainable levels, and we prioritize abstract “economic growth” over biodiversity and human well being. We’re going to need deeper structural changes to our economic system if we actually want to get serious about sustainability. Tesla is not helping bring about those changes. Bitcoin might be.

Green Tech

Tesla helps entrench and exacerbate a number of existing problems in the world.

One is American capitalism itself. There are obviously good ideas at the heart of American capitalism, about entrepreneurship, competition, and the power of mutually beneficial exchange to drive progress. But the modern incarnation of military-industrial, monopolistic, American consumerism is not particularly nurturing for a sustainable future. Tesla is perhaps American capitalism’s best foot forward.

Another is the supply chain of modern technology. The mining industry, for metals like Lithium, Coltan, and more, is riddled with environmental and human rights abuses. These are not so much measured in carbon emissions (though there are plenty) as in pollution and destruction of natural habitats and social relationships. And a car battery requires many orders of magnitude more Lithium than your Macbook. Clean energy has a very dirty supply chain, and little incentive to improve it.

A third is cars themselves. The complete centrality of cars in the organization of urban life is one of the great tragedies of our time. Sustainability is intimately bound up with how we organize ourselves on the surface of the planet. Cars, electric or otherwise, are not particularly conducive to the more human-scale and bio-diverse patterns that are critical to sustainability. To the extent that we have cars, they should probably be electric. But more than anything, we need less cars. Denmark has the right idea. As does anyone who’s ever gotten a street closed to cars, for any duration. Respect.

Now I’m not trying to dis Tesla, per se. Tesla is the beacon of a research and development process that is itself critical to sustainability. And if we want to make progress in batteries, which we should, cars are a great vehicle to ground that R&D. But the fundamental problems we’re facing today don’t seem so much technical as they do political-economic. More R&D in capitalist companies with dirty supply chains feeding conspicuous consumerism can only help so much.

Orange Money

Bitcoin, on the other hand, is a different kind of a thing altogether. Yes, Bitcoin is being exploited by American capitalism. Yes, Bitcoin mining hardware inherits the same dirty tech supply chain. And Yes, Bitcoin uses an extreme amount of energy. But as far as agents of structural institutional change at the global level for a more sustainable civilization go? Bitcoin might be the best thing we’ve ever seen.

That’s a pretty bold statement. And I don’t expect to fully convince you here. I merely intend to suggest that it’s worth thinking about. Bitcoin is taking its seat at the table of international monetary institutions. Its market capitalization today (~$900B), is larger than every one of the major American banks and payments companies. It’s also larger than most of the world’s national currencies, and almost as much as silver. Bitcoin is even set to become legal tender in El Salvador next month, and is under consideration for legal tender status in a number of other South American countries.

But Bitcoin isn’t a precious metal. And it’s not something produced by a company, nor a government, nor really any distinctly identifiable organization. Bitcoin is a collective. An open-source, verifiable, transparent, decentralized, collective hosting a store of value and a medium of exchange for all to use on equal terms without discrimination. Isn’t that the kind of stuff that sustainable human institutions are made of?

As a collective, Bitcoin shares more of its character with religion than with enterprise, more with performance art than with industrial production. This is true of all money: it is the materialized mythology of a society’s roots and values, its fruits and dreams. It is a means to bind society in a coordinated web of promises and their redemption. And Bitcoin is good art. The dollar, which has since been captured, corrupted, and calcified, was perhaps once good art too.

Some believe that Bitcoin’s philosophy stems from a kind of far-right market fundamentalism. And surely there is some truth to that. But Bitcoin emerged in response to the reckless behaviour and moral hazard in the banking system that precipitated the Global Financial Crisis, which put many millions of people around the globe out of work, evaporated their life savings, and paid out massive bonuses to the architects of the collapse. Bitcoin draws its life force as much from a more left-wing tradition of open-source collectivism and Institutional economics as it does from say the Austrian or Chicago schools. Bitcoin is as much Elinor Ostrom as it is Friedrich Hayek. It isn’t right-wing, it’s heterodox. That is to say, Bitcoin is for Progressives.

The Root of All Evil

Like any monetary institution, Bitcoin is designed to nurture a kind of trust among the members of the society it serves. But it does so in a very different way from the monetary institutions of the nation states. Many of the problems we face today, of inequality and sustainability, can be traced back to the institutions of money. Not that these issues are caused by our monetary institutions per se, but that they are greatly amplified by them. How is money created? Who is it distributed to? What is it distributed for?

Modern institutions of money have become enormously extractive and rent-seeking. They have brought about a tectonic decoupling between financial activity and the real socioeconomic activity of the human and natural world. Modern finance is notorious for its inherent instability and fragility, for fuelling unsustainable speculative fires, for exacerbating income inequality, for failing to adequately support essential labour and services in its value system. The monetary institutions of the nation states are intimately bound up in the mayhem wrought by the global financial system - they have thus dramatically betrayed the trust of the societies they serve.

At least some of this appears due to a collapse in the literal values of money as a representative media. Unmoored from any real world process, modern money multiplies monstrously under the machinations of central bankers. Its creation and distribution ceases to represent any meaningful or socially valuable information in the real world. As a device for transmitting value judgements, it thus becomes increasingly faulty. Modern Monetary Theorists will have you believe that they can rejuvenate the values of money by moving the printing press from the central bank to congress - but I have my reservations. Insofar as sustainable systems are those with sound representations of their environment within their own structure, our modern monetary systems are inherently unsustainable.

So what are we to do about this rampant inequality, about global unsustainability? We tried to Occupy Wall Street. We try to organize strikes, and to boycott corporations. We try to elect better politicians. We try to make individual life style changes, to bank at credit unions, to stop buying from Amazon, to invest in local community bonds instead of the stock market. But the problem of collective action remains. In a utopian dream, we’d all wake up one day and cease our destructive ways. But in practice, what can we do? How can we create real space for change? How can we create something new, a protest that cannot be shut down, an institution that enables coordination at global scale for a better political-economy? This is where new forms of money might have a real role to play. Monetary institutions are a gateway, a point of leverage, into the larger political-economic problems we face.

Bitcoin is the first, and so far most credible, attempt to challenge the current paradigm, to meaningfully innovate internationally in the basic values of money. Yes, it manifests largely as a speculative asset right now. But Bitcoin provides a new source of trust for international monetary institutions that is grounded, as we’ll see, in verifiable physical reality, in the thermodynamics of computation. While not perfect by any means (nothing is!), Bitcoin anchors a new generation of monetary institutions in one of the most fundamental physical processes underlying our civilization.

And Bitcoin is starting to find success as a fledgling monetary institution. This is not to say that it will or must necessarily become money for the whole world. But it is beginning to fulfill some meaningful functions of money in certain growing contexts - it’s being increasingly used to pay salaries, to make international payments and remittances, and as a highly liquid (though volatile) reserve asset on corporate balance sheets. It’s also finding increasing utility among the people of countries with unstable currencies and authoritarian governments.

Of course it’s also being used increasingly in ransomware payments and as fodder for speculative finance. In ransomware, it tragically illuminates the pervasive insecurity and fragility of the systems underlying our critical infrastructure. In finance, it fuels the same kind of leveraged and nebulous behaviour as the rest of the shadow banking system. Perhaps the greatest risk to Bitcoin is that it is swallowed up by Wall St.

Surely, Bitcoin is not alone the solution to the world’s monetary problems. It may be necessary, but it’s certainly not sufficient. I hold no pretense that Bitcoin will take over the world. I’m not even sure what that would mean or that it would be a good idea. But Bitcoin has unleashed, and proven the viability of, what is perhaps one of the most important ideas in political-economics in centuries - that money should be created by and for the people that use it. This is Bitcoin’s legacy. It proves the potential of money whose issuance and distribution is based, not on the liabilities of an unaccountable banking system, but on the values of a community, on the activity that network participants themselves determine to be socially valuable. In the case of Bitcoin, that activity is the energy intensive Proof-of-Work mining. But Bitcoin is just the first stage in a journey towards increasingly representative monetary systems that sustainably bridge the gap from local self-sufficiency to global luxuries and back.

In Proof we Trust

Bitcoin are created and issued to those who provably contribute to the security of the Bitcoin network via Proof-of-Work (PoW) mining. Proof-of-Work entails a specific kind of cryptographic computation resembling a numerical puzzle that is difficult to solve but easy to verify. If computing power were evenly distributed throughout humanity (which of course it’s not), Bitcoin’s Proof-of-Work mining would be a sort of Universal Basic Job, providing income to anyone who ran a Bitcoin miner. The energy used would be stable and proportional to human population.

Of course in the real world, Bitcoin mining is a highly specialized economic game played out in transistor sizes and electricity sources. Smaller, faster chips; cheaper, denser energy. The distribution of mining power is nowhere near uniform. Nevertheless, Proof-of-Work appears to be the best known manner to solve the problem of Sybil Attacks in open, permissionless, global systems. This makes it the best known mechanism to “fairly” distribute coins in a monetary system without strong identity.

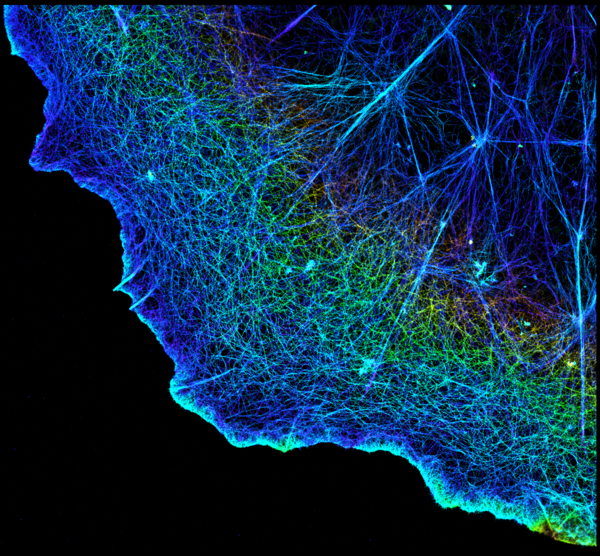

For years now, the Bitcoin mining network has been the world’s largest supercomputer, more powerful than all the other supercomputers combined, though it is computing only a single rather simple function with seemingly little practical value. So what do we even get for all this seemingly wasted electricity? What does Proof-of-Work mining really provide? We’ve already alluded to a kind of trust that this process produces, a guarantee sometimes referred to as thermodynamic immutability. It means that the integrity of the historical record produced by the Bitcoin blockchain (i.e. it’s immutability), is guaranteed by the thermodynamics of the universe, rather than the whims of our social politics.

It is often said that history is written by the victors, where victory is defined in terms of war and conquest. In this light the phrase reflects a sort of defeatist resignation to the perils of political plunder. But Bitcoin redefines that victory which writes history, not as discriminatory political might, but as a verifiable, thermodynamic process, at once accessible to all. It casts the same phrase in a more hopeful light, where history is written not by way of destructive political wars, but by way of a voluntary, collective, economic game.

As the Bitcoin blockchain marches on, the cost of re-writing Bitcoin’s history increases in proportion to the amount of computing power already spent. For this reason we talk about Proof-of-Work mining as providing a kind of security. Some call this kind of security “cryptoeconomic”, in reference to the mix of cryptographic and economic guarantees it provides.

This is not to say social consensus and politics are not involved in Bitcoin or that Bitcoin is just math and physics. Bitcoin is an evidently political-economic institution with many sources of trust. But the pumping heart of the Bitcoin network, it’s Proof-of-Work backbone, is a thermodynamic process that provides a kind of guarantee about history (“thermodynamic immutability”), and a kind of fairness in distribution (a sort of “universal basic job”) that we do not otherwise know how to produce. What we get from mining is the most advanced and robust source of trust for international agreement that we’ve ever had. And it only costs as much as the economy of Switzerland?! This may prove to be especially important in the coming years amidst what appears to be increasingly turbulent geopolitical relations. International sources of agreement are in short supply.

I like to argue that saying Bitcoin is wasteful is a bit like saying the Sun is wasteful. Look at how much energy the Sun wastes, and for what?! Of course, the sun provides a certain kind of guarantee to biological activity on Earth, a robust foundation for the development of all the world’s ecosystems. I suggest to you that Bitcoin, and the guarantees it provides, might play the same kind of role in our evolving digital ecosystem that the Sun plays for life on our planet.

Mind the Miners

Bitcoin mining gravitates to the cheapest sources of electricity, but the particulars are nuanced. On the one hand, there’s still cheap coal around, and miners are firing up old, dirty plants where they can get away with it. This is clearly bad. But on the other hand, renewables are increasingly the cheapest sources of power all over the world. Estimates of the carbon neutrality of Bitcoin’s mining power range from 30-70%. And apparently, El Salvador is planning to mine Bitcoin with clean energy from volcanoes. But these distributions are by no means static. We’ve witnessed recently the migration of huge amounts of mining activity out of China by virtue of the recent mining bans. Demand for cleaner mining operations is apparent and growing, as are projects to recycle heat generated by mining, for instance to warm greenhouses.

Further, the energy grid today intentionally wastes huge amounts of energy. As utility companies struggle to match the supply of produced energy to the demand for it, they often end up with excess energy that no one can use, energy with nowhere to go - it’s just wasted. This is true especially for solar and wind, which can only produce when the sun or the wind are present, but it’s also true more broadly. Utility companies may be able to use Bitcoin mining to help stabilize the grid by harbouring this excess, otherwise wasted energy. Many suggest Bitcoin mining might actually improve the viability of renewable energy projects themselves by functioning as a sort of quasi “battery” that can store excess electrical energy as financial value, and thus make profitable an otherwise costly mismatch between supply and demand.

As for Bitcoin mining hardware, the Application Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs), they may be simpler and require less extractive resources than car batteries and general computers, but their turnover has been quite substantial, as new, more powerful hardware hits the market every few years. E-waste in general is a very serious and growing problem globally, seemingly driven largely by two pathological but related tendencies at the heart of modern capitalism: planned obsolescence for consumers and inhibitions on the right-to-repair. The Bitcoin ASIC industry appears as a brutal caricature of these pathologies - each generation of ASICs becomes obsolete as soon as the next generation hits the market, and they require incredibly highly specialized production facilities. It’s also not at all clear yet how effective recycling is. These are all things to worry about.

But there is also reason to be optimistic. Bitcoin mining, and computing generally, are coming up against the physical boundaries of computation as Moore’s Law has started to break down, placing limits on the ability to produce new, faster chips without some kind of serious breakthrough in physics and computer engineering. This means the innovation must turn increasingly from speed (smaller transistors, more per chip), to efficiency, including more efficient energy usage, cooling, use of raw materials, etc. As microchip production is already a highly scarce resource, and priority is anyways given to major companies like Apple, Qualcomm, etc., Bitcoin ASIC producers have to make do with lower quality materials and longer delays. But In any case, by grounding itself in the most raw expression of computing capability, Bitcoin may even help to subsidize the production, and incentivize the decentralization, of computer chip manufacturing in general. The importance of greater, and more decentralized semiconductor production is being made increasingly apparent by the COVID induced shortage, which is causing all sorts of dislocations in the supply chain.

One could debate these nuances, around the energy, hardware, and economics of Bitcoin mining, indefinitely. Some do. The likes of Nic Carter and Lyn Alden making the case for, the likes of David Gerrard and Tim Swanson making the case against. But the limits to our reason and the dynamic nature of the industry frustrates any sort of final word on the matter. Bitcoin will ebb and flow, like any great technology, simultaneously threatening both destruction and salvation of the human species. We have only to ask ourselves, “Is the game worth the candle?”. And in this sense, the world faces much bigger problems than the energy usage and e-waste of Bitcoin. I think we’d do better to face those problems with Bitcoin at our back than without.

Bitcoin is no paper-clip maximizer. It functions instead as a kind of lens onto the rest of society. It’s core values, of freedom and self-reliance, censorship-resistance and verifiability, conservation and security, burn bright in contrast to the increasingly authoritarian and co-dependent quality of modern society.

Perhaps Bitcoin could be said to have the same kind of relationship to the world of semiconductors, energy production, and even economics as cannabis has had on hydroponics and agricultural technology - relative outcasts of a countercultural spirit, injecting massive amounts of R&D to swim between the cracks of existing institutions, ultimately transforming those institutions in the end for the better.

Big Bad Blockchains

Many people have heard the phrase “blockchains, not Bitcoin”, meant to express that blockchain technology is a meaningful innovation, but Bitcoin can be largely ignored. Of course, I don’t believe Bitcoin can or should be ignored. But it is also true, contrary to what many so-called “Bitcoin Maximalists” might avow, that blockchains, independent of Bitcoin, really are a meaningful innovation in their own right. Blockchains innovate in the field of fault-tolerant multi-stakeholder databases and applications, a field which is itself becoming increasingly important as we wrestle with the monopoly power of large corporations and the administrative overhead of more democratic institutions. Blockchains are tools of coordination, tools we can use to improve transparency, verifiability, security, privacy, reconciliation, and other complex and costly qualities of our social institutions. We should thus look forward to a proliferation of blockchains, perhaps on the order of the number of cities, or even the number of companies in the world, as a foundation for platforms that better represent and serve their stakeholders.

But does every blockchain need to use Proof-of-Work mining like Bitcoin? Absolutely not! In fact, there is little justification for more than a few Proof of Work blockchains, if not just the one. I’ve spent much of the last seven years (along with many other talented people) developing and promoting an energy efficient alternative to Proof-of-Work called Proof-of-Stake, where the competitive energy guzzling of miners is replaced by the collaborative pledging of validators. Instead of using energy-hungry Proof-of-Work, the integrity of the history in a Proof-of-Stake blockchain is guaranteed by having validators pledge their coins in a kind of “bond” which can be destroyed if they try to re-write history. To a large extent, this is what the Tendermint and Cosmos projects have been about. And we’ve largely succeeded. Pretty much all major blockchains being built today use Proof-of-Stake validators instead of Proof-of-Work miners, and thus do away with mining and the ridiculous energy expenditure therein. Many of them are even built using the Cosmos technology. There’s no real excuse for any new blockchain to use mining. Even Ethereum, which currently uses Proof-of-Work mining and is second only to Bitcoin, has begun its transition to Proof-of-Stake.

Proof-of-Stake, though, is not a panacea. Powerful as it is, it will never be able to provide the same guarantees as Proof-of-Work, no matter how close it thinks it can approximate them for practical purposes. And by necessity, Proof-of-Stake architectures are much more complex than Proof-of-Work. Like an order of magnitude or two more complex. There’s a lot to be said about the value and importance of simplicity in systems design. Compared to other chains, Bitcoin is also committed to a much slower pace of evolution. Some take this as a sign of ossification, as if Bitcoin is dead technology and cannot evolve. But Bitcoin in its history has managed to rapidly respond to software bugs, has gone through at least one major upgrade (“Segwit”), and has another upgrade scheduled this year (“Taproot”). As other chains experiment with more rapid evolution, Bitcoin remains committed to being a slow and steady backbone for the much larger ecosystem. Thus while Proof-of-Stake is unequivocally the immediate future of blockchains, Bitcoin’s Proof-of-Work, and Bitcoin itself, with its greater simplicity and commitment to a more conservative evolution, is not to be dismissed so quickly.

But Proof-of-Work and Proof-of-Stake are also not the end of the story. In my talk on Stakeholders and Statemachines, I propose that Bitcoin is the first stage in a journey towards increasingly representative monetary institutions, a fractal hierarchy of money that can sustainably bridge the gap from local self-sufficiency to global luxuries and back. That journey leads us from the more objective, international sources of trust, to the more subjective and local. From the cryptographically verifiable energy expenditure in a remote data center that is today’s Proof-of-Work, to the communally verifiable delivery of life sustaining care work that is tomorrow’s Proof-of-Care and Proof-of-Plant. Proof-of-Stake may be the next step in that journey - somewhat more subjective, less anonymous, more socially aware than Proof-of-Work.

But Proof-of-Stake is riddled with it’s own issues, many of which parallel the oligopolistic tendencies of modern finance, of which we have not the time to address here. What Proof-of-Stake blockchains do give us today, though, is an environmentally friendly platform on which we can discover and experiment with new monetary primitives, ways to incentivize, for instance, regenerative agriculture, cooperative internet service providers, mutual credit unions, and local money alternatives more broadly.

Conclusion

Monetary institutions are not static. They evolve considerably. And they have profound effects on the socioeconomic structure of society. Bitcoin’s Proof-of-Work mining provides the most advanced and transparent source of trust for international institutions yet known to our species. It applies a consistent sort of evolutionary pressure on our institutional forms towards the more verifiable, accessible, and representative - that is to say, the more democratic. It suggests that our international institutions could be grounded, not in military prowess and colonial conquest, but in our ability to harness energy for computation. And it suggests a layering, a fractal hierarchy of money, stretching from the more objective and anonymous work of harnessing electrical energy, to the more communal and self-sustaining work of growing food and caring for each other. It is on the basis of this more humane foundation that we might expect to build a more sustainable society. Surely, this is something much better for the world than a capitalistic electric vehicle manufacturer.

Special thanks to Jackie Brown, Gregory Landua, Rick Dudley, and Shon Feder for reviewing drafts of this article.